WORLD COMMUNITY for

CHRISTIAN MEDITATION

WCCM Norge

Kristen meditasjon

Hva er kristen meditasjon?

Hvordan vi mediterer

Jeg vil sitte

Jeg vil tie

og jeg vil høre

hva Gud sier i meg.

Meister Eckhart (1260 – 1327)

OM Å MEDITERE SAMMEN

Det er så enkelt, så lite kravfullt, så ekte, så intenst, så kraftfullt, så helende.

Og de som kommer, er de som skal komme. Og det er så vakkert, så riktig,

så rett til hjertet. Akkurat det jeg - vi - trenger.

Ikke mer. Ikke mindre.

Easter Sunday

Happy Easter. And finally, we can say Alleluia again! One word says it all.

St John looked into the empty tomb and let Peter, his companion whom he had outrun to get there, go in first. Peter, the good but less subtle part of us. Then John, the lover in us, went in and ‘he saw and he believed’.

As I have been writing these reflections during Lent I have had an invisible companion, no doubt part of myself, who is not merely a non-believer but who does not just ‘believe’ either. This is an important part of ourselves to befriend and learn from because its questioning curiosity gives space for faith to grow and teach us things we never dreamed of before. We become enthusiastically inauthentic if we just jump up and down saying we ‘believe’. Anyway, the word we translate as ‘believe’ has much more content and outreach of meaning – to have faith in, to be persuaded, to trust. The English word ‘believe’ grows from the word ‘love’.

Something bursts today in humanity’s journey into consciousness, long imagined and much hoped-for. It is not like the working out of a solution to a maths problem or even like finishing a work we have been long engaged on. It is more like the bursting of a seed or the opening of a flower. It can best be recognised if we allow it, moment by moment, to persuade us that it understands us.

‘He comes to us hidden and salvation consists in our recognising him,’ Simone Weil said.

It is like seeing what makes a joke funny or why a pun can both please and irritate us. We don’t have to try too hard, just wait for the penny to drop. Today is just the beginning and if the beginning is so good imagine what the rest will be like.

I hope these Lent Reflections have been of some service for you during our long trek. I would like to thank the great team, led by Leonardo, who got them distributed and very specially the translators who patiently (I think) put up with some last-minute deliveries and for their very generous gift of time and wonderful talent.

One word says it all. Happy easter.

Laurence Freeman

Palm Sunday

In the coming days we are invited to encounter the power of an ancient tradition that makes a particular period of time sacred: we call it ‘holy week’. It culminates in the final three days in the transcendence of time, the bursting of the eternal present into the human dimension of time and space.

If we can feel it as an invitation, we could experience hospitality in its fullest meaning. Today the ‘hospitality industry’ means pubs, restaurants and hotels and is an important part of the economy in the service sector. Spiritually and in traditional societies, however, hospitality is an experience of a mysterious relationship in which roles are reversed and oppositions are entwined.

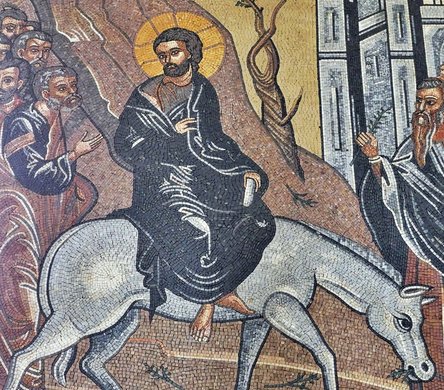

Today, Palm Sunday, remembers the triumphal welcome of Jesus into Jerusalem. The crowd of pilgrims who had come for the religious festival went wild and he seemed to be riding high in a way that a celebrity or a politician longs for. People wanted to see the man reputed to have raised the dead. Ironically, Jesus rode in not on a beautiful white horse but on a donkey. In a few days, the crowd had turned against him and were clamouring for his death as a blasphemer. That hospitality of Jerusalem proved shallow and false.

The root word for hospitality is the Latinhospeswhich oddly contains three meanings: guest, host and stranger. Stranger also hints at ‘enemy’ and linkshospesalso to the word ‘hostile’. Strangers are visitors from the foreign and the unknown. Maybe they are potential friends. But don’t trust them yet, even if they come bearing gifts. Prudence says treat them as friends, even as divine visitors. In some cultures, the welcoming host become responsible for the safety and well-being of the stranger whether they need a hotel or a hospital. In India the principle ofAtithi Devo Bhava, the guest is God, must always be respected. In Christian communities the guest must be welcomed as if they were Christ himself and in a few countries this even applies to immigrants. The Qu’ran says that even prisoners of war should be treated like guests

Strangers pose possible dangers; and maybe the social custom of exaggerated hospitality is a way of protecting the host from them. But deeper than this fear is the vision of God present in in everyone. That insight arises from the simple and universal experience of human kinship. Some theories say that there is a hidden hostility in hospitality as it distances us from the stranger. But beyond theory, in the practice of gracious, courteous welcoming the projections of divinity or danger on the guest can be resolved. The Christ in me welcomes the Christ in you. Human relationship moves into a higher level, almost the highest level of nondualism. In this atmosphere, fear, division, conflict cannot survive. There is peace and unity.

If we see Holy Week as an invitation, then, we may soon find this peace even through the intense changes of mood and the tragic-transcendent conclusion of the following days. We will make a passover from a vision of life seen through the prism of fear to one of confidence and trust. I saw the almost full bright moon just now, walking out after meditation. She is both guest and host and a familiar stranger.

Both Passover and Easter festivals are controlled and reconciled by her. She is full-faced, innocent and lovely and you can bask in her cool healing light without any fear.

Laurence Freeman

I

Advent Reflections 2023 from Laurence Freeman

First Sunday 3rd December, Mk 13:33-37

Jesus said to his disciples: ‘Be on your guard, stay awake, because you never know when the time will come. It is like a man travelling abroad: he has gone from home, and left his servants in charge, each with his own task; and he has told the doorkeeper to stay awake. So stay awake, because you do not know when the master of the house is coming, evening, midnight, cockcrow, dawn; if he comes unexpectedly, he must not find you asleep. And what I say to you I say to all: Stay awake!’

This teaching expresses the spirit of Advent. Like Advent, it is not about delay or abstraction. Yet, it’s hard to see what the simple instruction to ‘stay awake’ really means. If we don’t see what it means how can we obey it? The master has left his servants alone. This is like the feeling that God is personally absent but still impersonally present in the laws of the universe or Murphy’s Law (if something can go wrong it will).

I was travelling to spend a weekend alone on retreat before a medical operation. I discovered on arrival at the airport that my bag had been stolen from the train. I had to report it in French to an official who could not take his eyes off his mobile phone and treated me with barely-concealed contempt. Then the flight was long delayed. I decided to use the opportunity to get a gadget which I had long needed or at least wanted. I set it up successfully and then it promptly died on me. Real, sudden, unfixable inoperancy. The next day I had to go back and waste hours at the nightmarish shopping mall to get it replaced. My retreat weekend was ruined and why did I feel to blame? Getting to hospital was almost a relief because something seemed so intent on obstructing me. The day after the operation I lost my glasses causing great inconvenience for more than the week it took to replace them. I was obliged to be patient (who could I be angry at?) but there was a sad sense of a pattern of hostility.

I wasn’t complaining. But was I imagining a pattern? No, they were real events, even if they reminded me of Murphy’s Law that ‘if something can go wrong it will and at the worst possible time.’ It felt more humorous than hostile. Was I expected to understand this oddly linked set of events? No, I simply had to embrace them indifferently, impersonally, without judging or explaining them without resentment which is a mask of anger.

Maybe this is what ‘staying awake’ means. After all, who are we? Servants, not self-employed, less like a snobbish butler, more like a house-slave. Not understanding the master’s will and yet having to accept and obey it produces at times a cold impersonality. The master is absent and we don’t know when he will return and end the run of bad luck. But come home he will. This still feels a shallow, literal interpretation and not what Advent as a spiritual practice is about. It is not Father Christmas but the invisible Master who returns on Christmas Day. If birth is really a return, everything has a purpose.

Uncomplaining, generous acceptance may seem beyond our capacity. Nevertheless, the lesson is always: more humility. Simone Weill said ‘humility is attentive patience’. In misfortune we learn to be ready for the unexpected. Our wakefulness, then, becomes joy.

Refleksjoner fra Bonnevaux 2022 ved Tone Mjaavatn

I 2022 deltok fem av oss som mediterer i WCCMs grupper her i Norge på retreat på

Bonnevaux for første gang. Det har gjort sterkt inntrykk.

Vi har ventet lenge. Denne retreaten ble planlagt for høsten 2020, men ble, på grunn av

pandemien, utsatt til nå. Så det var godt endelig å få opplevd stedet. Og miljøet rundt det.. "I feel Bonnevaux is a place of serenity", sa taxisjåføren som en lys, varm ettermiddag hentet oss i forhåndsbestilt drosje fra Poitiers etter at vi hadde ankommet med TGV-tog fra Paris. "And I like that very much"l

Det gjorde vi også. Og vi skjønte fort at han hadde rett. For det første som møtte oss da vi kom frem var nettopp roen. Vi tenkte på det som stillhet, men veldig stille er det egentlig ikke på Bonnevaux, ikke ute i hvert fall; fuglene synger uavbrutt, sikader og frosker holder på, bier og humler også, og lyden av et tog og et og annet fly gjenkjente vi også iblant. Likevel hviler denne stillheten, eller roen, sjelsroen, over hele stedet, ute og inne. Det kjentes som en kraft, en omtenksom, vennlig kraft: "Vær stille, og kjenn at jeg er Gud".

Vi merket det i låven, der vi deltok i kommunitetens faste bønn- og meditasjonsliturgi, i

spiserommet der alle måltidene var tause unntatt middagene. I begynnelsen ønsket jeg meg lav musikk til maten, men det forandret seg da vi lærte å konsentrere oss om det som er vårt (på vår tallerken) og ikke la oppmerksomheten drive mot naboen(s gaffelklirring).

Og i naturen. Langs skogsveiene, gangstiene, langs vide åkre og intenst blomstrende enger. På

Korsveien, ved den lille innsjøen vi har sett så mange bilder fra hjemme. Under de enorme, eldgamle trærne der vi innimellom satt og småpratet lavt eller leste eller undret oss alene når solen var på det varmeste. Var det ikke 400 år gamle de var?

I atmosfæren. Tross mye arbeid og sikkert vanlige frustrasjoner bak kulissene: i vennligheten og

imøtekommenheten fra både faste og frivillige som er kommet fra hele verden for å hjelpe

til på hver sin måte og være en del av dette. Noen som fast stab, andre som mer

kortsiktige husfolk. I hjelpsomheten når vi ikke fant frem, i smilene oss alle i mellom når vi

ikke fant ordene. Latteren, som vi av og til ikke kunne dy oss for, i Giovannis yogatimer,

eller ved middagsbordet der vi kunne bli litt kjent med hverandre. Kjøkkendøra ut til hagen

som sto åpen til sent på kveld og viste at det var folk der. Lettelsen og gleden over å så

lett bli inkludert i - og oppmuntrende utfordret av - dette fellesskapet, ikke minst gjennom

våre daglige små (hus)arbeidsoppgaver, for visst er dette et sted for bønn, men også for

arbeid.

Og i arkitekturen. I de små detaljene fra den gamle "Abbyen", i det lille kapellet fra det opprinnelige klosteret, i låven, som også var stedet for yogaøvelser og fr Laurences grunnleggende foredrag, i den gamle stallen som nå inneholder gjesterommene, kjøkken og spiserom, bibliotek, den lille bokhandelen, kontorer …

Dette var en av de første retreatene på Bonnevaux etter pandemien og ferdiggjøringen av første etappe i restaureringen av dette tidligere Benediktinerklosteret fra 1200-tallet. Da WCCM kom over det for 6 - 7 år siden var det som å komme hjem, fortalte fr Laurence. Et stort arbeid ble satt i gang, finansiert av velvillige donasjoner. Blant annet ble alt arkitektarbeid gitt gratis av en vel anerkjent (mediterende) arkitekt i Singapore. Stedet er blitt imponerende nennsomt vakkert og funksjonelt restaurert - så langt; Det foreligger planer for mye mer.

Så var det Labyrinten.

Dette gamle kristne symbolet ble vårt tema disse dagene.

Som fr Laurence underviste oss i, så vi forsto viktigheten i

å gjenkjenne forskjellen på en kanskje fristende "maze"

(den ble illustrert med noe som kan likne en QR-kode, det

nærmeste norske ordet er kanskje "forvirring") der livet

virker fritt og fristende fullt av valg, men også (ofte

underholdende) distraksjoner, men som er uten kjerne, og som vi etterhvert blir slitne og mismodige av å befinne oss i, og en labyrint, som kan virke lukket og fastlåst fordi den bare består av én vei, én liten smal sti. Men som leder til livet. John Main kalte det å praktisere meditasjon "en pilegrimsvandring til det helligste stedet i verden. Og det helligste stedet i verden er menneskets hjerte". Labyrintens sentrum.

Det syntes vi at vi merket da vi, etter å ha satt labyrinten sammen steinplate for steinplate i

stekende sol over flere timer, en sen ettermiddag kunne bevege oss langsomt fremover innenfor de begrensende, men også klargjørende grensene den består av, helt inn til midten, med "mantraet som nøkkelen som hjelper oss å holde retningen". Der ble vi stående i kveldssolen, og holde hverandres hender. Svalene sang, sirissene spilte, en og annen humle surret. Vi hadde ikke ord.

Noe la seg til ro i oss der på Bonnevaux, på dette gamle, gamle klosterstedet. Og noe

våknet i oss. Noen ante at en indre helingsprosess kunne være på gang. Noen snakket

om "to unfold". Noen om å komme til rette med seg selv, finne veien og tørre å gå den. Noen om velsignelse.

Selvfølgelig var det rart å komme hjem. Selvfølgelig var det rart å oppleve at livet her

fortsetter som før.

Men det gjør ikke det. For oss. Ikke helt. For det er noe med denne atmosfæren på

Bonnevaux, livsnær, skapende, uhøytidelig og seriøs, båret av stillheten og denne roen,

sinnsroen, som ligger under hele tiden, den som taxisjåføren fra Poitiers snakket så

hengivent om, som har inspirert oss dypt. Som kanskje er det som modner oss for denne

livserkjennelsen, dette Kristusmøtet, som ligger i kjernen av denne urkristne

meditasjonsformen vi holder på med. Som i labyrinten. Og som vi jo har visst om, men

som vi gjenopplevde så tydelig på denne retreaten. Og som vi ikke vil gi opp, men gå mot,

ta i mot. Hver dag. Hver meditasjonsstund.

Kontakt WCCM Norge:

wccm@wccm.no

Tlf: 95 20 66 64 (Tone)

Velkommen til å utforske vår side på:FACEBOOK (facebook.com/WCCMNorge/)

Kontonummer 1822 76 19658 VIPPS: 51 20 00 eller WCCM Norge